This past August, Charlie Michaels (MFA í11), Coordinator for Detroit Connections, led a group of 10 undergraduate students from the Stamps School on a three-week international experience in Ghana, West Africa.

When I went to Ghana for the first time in 2009, I had no idea that I would keep ďgoing and coming,Ē as Ghanaians say. But there is something about Ghana that always pulls me back, mentally and physically. Iíve been told, ďThere is a rhythm to life in Ghana, both literally and metaphorically, and once you get in step, you fit right in. Itís difficult to explain, but itís something that you can feel.Ē It can be challenging, but if you allow yourself to submit to the flow of everyday life in Ghana, itís easy to get addicted to the rhythm.

This was my third trip to the country and, for me, the most exciting yet. I had the privilege of watching students step into the rhythm of Ghana themselves, during what was, for many, their first time traveling internationally. And I had the pleasure of sharing with them this place that Iíve grown to love and feel at home in.

Arriving in Africa

After landing in Accra, we travelled to Nungua, a fishing village nestled on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, just east of the capital city. Nungua is a fairly large village connected to Accra by a busy main road. Itís an active place, but peaceful, made up of streets dotted with tin-roofed homes and shops, a bustling market, red sand football fields and breathtaking views of the sea. Nungua is my base in Ghana, my place to come home to.

In Nungua we stayed at a place known locally as Aba House, for the woman, Aba, who founded and runs its programs. Aba House - or, officially, Cross Cultural Collaborative - is a cultural center and guesthouse in Nungua that organizes workshops for local children in papermaking, bookbinding, ceramics, computer skills, literacy and traditional Ghanaian art forms. Kids come from around the village to work on projects under a big beautiful tree whose branches extend to create a canopy of leaves over Abaís yard.

Three Weeks, Three Projects

With guidance and input from Aba about the goals of the organization and what was needed in the community, we decided on three projects for our time in Nungua.

1. Engaging With the Local Children: Paper, Prints, and Paint

Cultural understanding doesnít come from simply witnessing another culture. It comes from friendships, from conversations, from teaching and learning... - Abby Bennett

Kids at Aba House have been making paper for years out of the leaves from sugarcane that grows in the front yard. They use the paper to bind books that have covers stamped with ďadinkraĒ, traditional Ghanaian symbols. As years pass, older kids teach the younger kids this lengthy process which builds dexterity, focus, and work ethic. The handmade books are sold in Accra and abroad and the proceeds come back to the kids in the form of their school fees and supplies.

Abby, Leah, Rachel, and Cori started their work in Nungua as apprentices in the papermaking processó cutting, drying, and boiling the leaves, then rinsing them in the ocean, pounding them into a pulp with a wooden mortar and pestle, pulling the paper, and drying and pressing the sheets.

Friendships were formed quickly and other projects started to develop.

As our work together developed, the design for a mural emerged. Painted on the interior stairway of Aba House, it tells the story of our groupís time in Ghana, drawing inspiration from games played with the kids and the imagery that came out of the various projects we did with them.

2. Engaging With Local Artists: an Artistsí Map

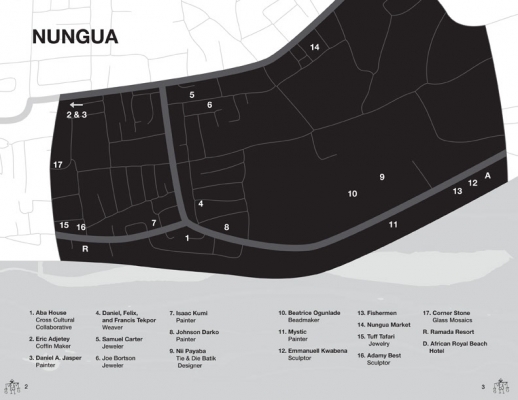

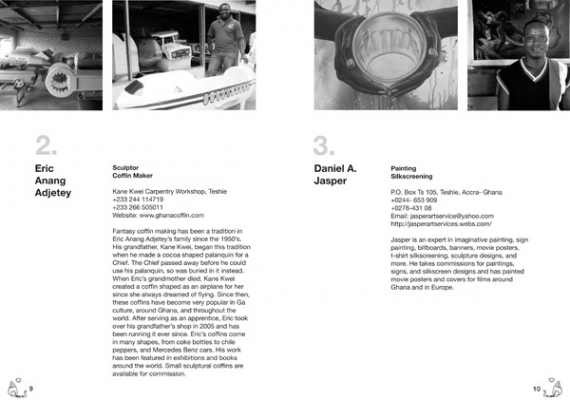

There are many artists and craftspeople working in Nungua, contemporary and traditional - weavers, potters, bead makers, jewelers, sign painters, fantasy coffin makers, etc. Some have small studios or shops and some work out of their homes or yards. Many sell their work to middlemen who then sell it at markets in Accra or abroad. One of the goals of Aba House is to support local artists by offering them resources and workshops and promoting their work.

Hannah, Tarah, and Jenny began working on an artistsí map of the village so that tourists could navigate their way through Nungua to look at and purchase work directly from local artists.

Getting out and interviewing people was the first step. With various local artists and children serving as guides and translators, the mapping group went off into the village to meet artists and craftspeople and see what they were up to.

As our list of artists and craftspeople grew, the places they work and sell were recorded on a map of the village. We added descriptions of their work, bios, and contact information for each and compiled it all into a booklet that also featured drawings by Aba House children.

At the end of our trip, Hannah and Tarah presented a copy of our map to the Chief of Nungua, Nii Bortralabi Borketey Laweh XIV.

3. Environmental Solutions: Making Charcoal from Corn Cobs

I think some of my favorite moments were seeing people getting excited about the charcoal, especially elders like BenÖ You could tell they really understood the project's potential for helping a lot of people. - Wes Wittry

Making charcoal out of agricultural waste is an environmentally friendly solution to the ongoing need for cooking charcoal in West African communities like Nungua.

This process, developed by the D-Lab at MIT, is easy to learn and is similar to the papermaking process in terms of steps and tools. It also addresses, on a small scale, some of the problems that arise out of the production of charcoal from wood, like immense deforestation. Charcoal derived from wood is the most commonly used fuel for cooking and heating in Ghana.

We decided to learn the process for ourselves and teach it in Nungua to whoever was interested in learning, with the hopes that it could spark an entrepreneurial venture for the right person.

The process involves burning plant material (in our case, used corn cobs), crushing the burnt material into a fine black powder, mixing it with a binder made from a starch like cassava, and packing the mixture into a handmade press that compacts it into a nicely formed briquette.

Alana, Wes, and Diane worked on making charcoal in Abaís front yard, troubleshooting the process with new materials. Many people who came through the yard during the day saw great potential in the new technique. At the end of every batch, we gave briquettes away to neighbors to try out and encouraged people to come work with us. Talk True, the full time caretaker of Aba House, Ben, a retired school administrator, and Nortey, a friend of Benís, were the most eager to learn and troubleshoot with us and share the knowledge with others. As Alana observed, ď...what weíre doing feels sort of like developing electric cars. Someday it may be of great importance.Ē

What We Learned

Though the projects we worked on with people in Nungua had, and will continue to have, an impact on the community, I feel like it was really we who learned the most. Our three projects were the mediums through which we were able to form connections with people, have new and challenging conversations, navigate new situations, and gain an understanding of daily life in a Ghanaian village.

Life here has been joyous and difficult. Fruitful and painstakingly tedious. Full of ease and full of discomfort. Sometimes I feel myself blending into the pattern that is Ghana and at others I am like a puzzle piece that just wonít fit. I belong and I do not. The contradictions of my existence here provide for a lot of conversation, processing, and of course, learning. - Alana Hoey

The give and take that occurs when working with new people in new environments is continually humbling - especially in small moments - when asked to do something that challenges your comfort zone, like dance in front of people, or when a child offers a solution to a problem that you had never considered.

As artists, designers, and human beings, these valuable moments of connection, confusion, frustration, failure, and liberation require us to process and make sense of our own desires, expectations, and assumptions about the world.

Watching these moments unfold and observing relationships develop over the course of the three weeks, both within our group and with the people of Nungua, was the most rewarding part of the experience for me. Itís a short amount of time, but it is incredible how much we were able to accomplish both with others and within ourselves.

After you immerse yourself in a culture for an extended period of time, especially one thatís so different from your own you canít possibly be the same. So then comes the challenge of figuring out how you live your life now that you know so much exists. - Rachel Junker

I want to give special thanks to my friends in Ghana for their hard work in making sure this experience was unforgettable Ė Ellie (Aba) Schimelman and Talk True of Cross Cultural Collaborative, Ralitsa Diana Debrah, Musa, Ben Adipah, George Kushiator, and Nani Agbeli.