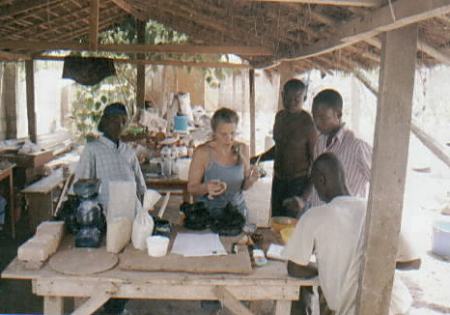

Raku Workshop, August 2003

Raku is a ceramic technique of removing items from the kiln while they are still hot and submerging in saw dust or other combustible material. The result is a metallic glaze. No two pieces are alike so there is always a feeling of expectation while waiting to see the results.

The technique lends itself well to African sculpture because unglazed surfaces become dark from the smoke.

Raku is not common in Ghana. Barbara introduced it with the intention of making it possible for the Ghanaian potters to continue using the technique. She demonstrated how to build a portable kiln using materials available in Ghana and, although she brought some glazes from the States, we experimented with glazes available in Ghana and found some of them to be suitable.

An interesting cultural hurdle was to convince the Ghanaian potters that they could use raku to their advantage. Although beautiful, raku pots are not functional and that is the problem. Africans do not use pieces for decoration. Everything is functional! We partially solved this problem by encouraging them to raku sculptural pieces. We feel that these pieces will sell in gift shops and galleries because of their uniqueness. This workshop will continue next summer. Barbara might go to a pottery village and introduce the technique to some indigenous women. All potters in Ghana, both contemporary and traditional are looking for ways to revive a weak industry.

Barbara's report on the workshop

In August of 2002, while facilitating the clay furniture workshop for the Cross Cultural Collaborative, there was a keen interest expressed by Ghanaian ceramists to experience American Raku.

This firing technique developed in Japan in the 16th century is characterized by fast firing work to 1850 degrees F.

The glazed pieces are quickly removed with long tongs and placed into a metal can or earthen pit lined with combustible material.

The pit or can is swiftly sealed setting up a reduction; or low oxygen atmosphere. This causes the glazes to become iridescent, and in some cases take on a high copper luster. While this may sound like an easy feat,

putting your body close to an open fire burning at that temperature and removing molten work takes some practice and quite a bit of courage.

The glazed pieces are quickly removed with long tongs and placed into a metal can or earthen pit lined with combustible material.

The pit or can is swiftly sealed setting up a reduction; or low oxygen atmosphere. This causes the glazes to become iridescent, and in some cases take on a high copper luster. While this may sound like an easy feat,

putting your body close to an open fire burning at that temperature and removing molten work takes some practice and quite a bit of courage.

What was to be a four-day workshop continued for over a month with many day and evening firings. This gave participants interested in continuing the technique plenty of practice. I had brought several glaze chemicals and a venturi burner to get us started. The materials to build the kiln were purchased locally. We were delighted to find that some of the enamel glazes available in Ghana showed promising results and a facsimile burner could be easily reproduced. The Ghanaians are very innovative when it comes to adaptation of materials.

Most innovative of all were Kingsly and Eddie, kiln builders who had come to re build Aba’s gas kiln.

They were very interested in learning to build the raku kiln and became valuable members of our workshop. Eddie is a very talented sculptor and the raku process lent a magical quality to his work.

Kingsly quickly became an expert at pulling the work from the fire. He loved the excitement of the process and the words “no fear” come to mind as I picture him shirtless with sandals; his charming

smile defying all of my safety rules. But then, “this be Ghana” and it seems the rules we use in the States need not apply! The only safety precaution our participants were willing to follow was one

that came with a fashion statement: Bandanas, Red white and blue with stars on top. Kingsly called me “The Sergeant” as it seems I barked orders during every moment of the firing process.

I must say in my defense that the process needs to be choreographed very carefully with contingency plans in place. You have only a few seconds to remove the work or it becomes too cool for the glazes to

mature properly and the work could be lost. Everyone had to be ready to do his or her job and be alert because going to plan B at a moments notice could easily become necessary.

Most innovative of all were Kingsly and Eddie, kiln builders who had come to re build Aba’s gas kiln.

They were very interested in learning to build the raku kiln and became valuable members of our workshop. Eddie is a very talented sculptor and the raku process lent a magical quality to his work.

Kingsly quickly became an expert at pulling the work from the fire. He loved the excitement of the process and the words “no fear” come to mind as I picture him shirtless with sandals; his charming

smile defying all of my safety rules. But then, “this be Ghana” and it seems the rules we use in the States need not apply! The only safety precaution our participants were willing to follow was one

that came with a fashion statement: Bandanas, Red white and blue with stars on top. Kingsly called me “The Sergeant” as it seems I barked orders during every moment of the firing process.

I must say in my defense that the process needs to be choreographed very carefully with contingency plans in place. You have only a few seconds to remove the work or it becomes too cool for the glazes to

mature properly and the work could be lost. Everyone had to be ready to do his or her job and be alert because going to plan B at a moments notice could easily become necessary.

James an amazingly gifted self-taught sculptor was with us everyday. When he was not working on designing and constructing a cement Juju tree in the middle of Aba’s dining room, he was sculpting figures in clay depicting both traditional and contemporary Ghanaian life. His works were remarkable on their own but when removed from the raku pit they took on Reverence. This seemed to be the perfect medium for James to express his art. James kept us mesmerized by his stories of Ghanaian culture and his lovely demeanor and winning personality made him a joy to work with.

Happy Kufe, founder of Unique Ceramics, a successful business that imports both traditional and contemporary Ghanaian ceramics to Europe and the States joined us as well. The day I was heading home Happy called to say that he had some European clients ready to put in a large order for his future production of Ghanaian Raku pots.

There were many fellow Ghanaian artists that I had worked with last year that joined us during some of the firings.

Through E-mail we were all just a click and we kept in touch through the year sharing our work and nurturing our friendships. It was wonderful to see, work, (and laugh) with everyone again. Nungua is an arts and crafts

community and it is easy for artists from any part of the world to feel at home. Here one truly leans that art is a universal language that crosses all boundaries. I was also very blessed to have a few days with my

friend Dora Mensa an indigenous potter from the Volta Region and Sammy Ansi who had facilitated the clay workshop with me last summer. Sammy and Dora are working on plans to bring Raku to the Woman Potters Association of their region.

There were many fellow Ghanaian artists that I had worked with last year that joined us during some of the firings.

Through E-mail we were all just a click and we kept in touch through the year sharing our work and nurturing our friendships. It was wonderful to see, work, (and laugh) with everyone again. Nungua is an arts and crafts

community and it is easy for artists from any part of the world to feel at home. Here one truly leans that art is a universal language that crosses all boundaries. I was also very blessed to have a few days with my

friend Dora Mensa an indigenous potter from the Volta Region and Sammy Ansi who had facilitated the clay workshop with me last summer. Sammy and Dora are working on plans to bring Raku to the Woman Potters Association of their region.

Introducing Raku for only one month barely scratched the surface of what can be done with this technique in Ghana. Now that the excitement and magic of the initial discovery are over, it will be time for those interested in pursuing the process to begin some serious testing of local clay bodies and glazes. It is my hope that co-operatives will be formed so that resources can be pooled to purchase the supplies needed for building the kiln and securing glaze chemicals. Raku could then give a new dimension and source of income to the Ghanaian Ceramist.

-- Barbara J. Allen

![]()