In Ghana,

Pottery is

Women's Work

A visitor learns about pottery and living in a mountain village

first published in Studio Potter

by Ellie Schimelman

A couple of years ago I went to Mpraeso for the first time. I had asked my friend Felicia, who lives in Accra, Ghana's capital, if she would take me to her village, which is famous for its pottery.

Mpraeso sits on a mountain plateau about three hours' drive north-west from Accra. We went there on a bus, which was elderly and missing a few of its shock absorbers.

Technically African busses hold five passengers in each row. In reality they also hold an unlimited assortment of children, trussed chickens under the seats, and luggage. It's usually a tight fit. The busses operate on "African time" and will not depart until they are filled, so a posted 10 a.m. departure time is only accurate if the bus happens to be full at 10 a.m.

For an American it's not a comfortable ride, but in return for the heat, the crowd, and the bumps, you find yourself included in the instantaneous community of the bus. Everyone talks to everyone else, generously giving their unsolicited opinions on overheard conversations. Some sing, others eat, while occasionally someone will stand up front next to the driver and try to sell the passengers cures for everything from bad breath to cancer. I am always impressed that customers will pass money up the length of a crowded bus, and the money will reach its destination unscathed.

Headlights are for sissies

After a long, hot ride, the bus left Felicia and me in a busy car park, where we were instantly surrounded by taxi drivers yelling, "Mpraeso! Mpraesol Over here! Over here!"

We found ourselves finally in one of the taxis with four other passengers. Though by now I've experienced the phenomenon many times, I still marvel at the number of people that can fit into an African taxi.

From the outside it's just a regular, though older and sadder taxi, but inside it's more like a circus car, holding a seemingly infinite number of passengers. Without the hidden trapdoor. Legally a taxi may hold only four passengers and the driver, but nobody obeys this law, though some do acknowledge it exists.

A potter at work. Pottery, like nearly every village activity, takes place outdoors in the communal yard, preferably in a patch of shade.

A potter at work. Pottery, like nearly every village activity, takes place outdoors in the communal yard, preferably in a patch of shade.It was dark when we finally left the car park, but I could feel we were already going uphill. As the climb became steeper, the road signs got more and more ominous - "go slow," or "dangerous curve ahead," with some nicely-placed, hand painted skull-and- crossbones signs for emphasis. A quick glance out the window confirmed my hunch that any vehicle not able to make it around the next curve would drop right off the road, returning to the valley below rather faster than it had climbed up.

There was a lot of traffic in both directions. Some drivers seemed to think headlights were only for sissies. Some felt it necessary to Pass every car in front of them, regardless of speed. It wouldn't surprise me to learn they were training for driving in Boston.

I found myself wondering why I'd thought it would be fun to visit Mpraeso. At least, I comforted myself, I'd only have to repeat the journey once more for the trip down.

Eventually the landscape again leveled out; we had actually reached the plateau. In Accra, down on the coast, the weather had been hot and humid, and the cool mountain air felt refreshing. After all that jouncing around and my sheer terror in the taxi, I was looking forward to a good night's sleep. Tucked into bed at Felicia's aunt and uncle's house, I was just drifting off when Felicia said, "Because it was so dark, we'll go back down the mountain tomorrow so you can see how beautiful the scenery is on the drive up."

I passed an uneasy night.

"Slowly, slowly ..."

The next morning Felicia began by bringing me to meet Akua Manu, one of her relatives, who is a traditional potter.

(Exact family relationships are often puzzling for outsiders; terms like "mother," for example, may he terms of respect as much as descriptive of actual fact. Until I figured this out, I couldn't understand why Felicia, for instance, would have six "mothers.")

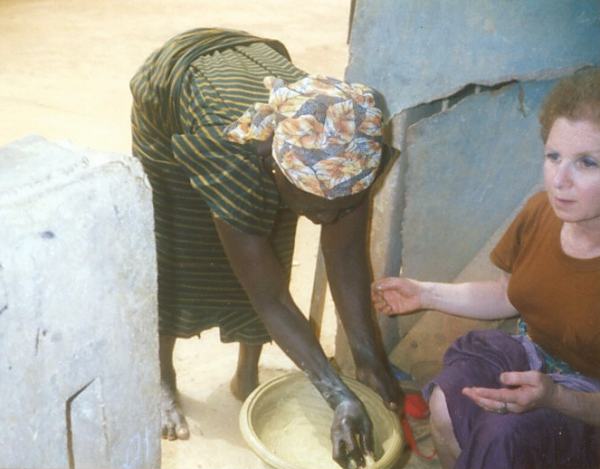

Akua Manu makes some adjustments in Ellie's bowl

Akua Manu makes some adjustments in Ellie's bowlAkua Manu and I liked each right away. She doesn't speak English, but with Felicia as interpreter and plenty of body language, we managed to communicate. When I said I had come to learn how to make traditional pots, she offered to teach me.

Kakra, kakra.... slowly, slowly. We start with a pinch pot. The walls must be of even thickness. Scoop the clay from the inside base and wall. Coil it onto the rim to keep the edge from stretching too thin and cracking. Bits of cloth or leather, or a small corncob, are dipped in water and used to smooth the walls. Kakra,...kakra....

Different villages make different pot shapes. Mpraeso is noted particularly for its grinding bowls, shal- low dishes with strong, inverted rims and ridges on the interior. A small wooden pestle is used for grinding - tomato, pepper, okra, whatever is required.

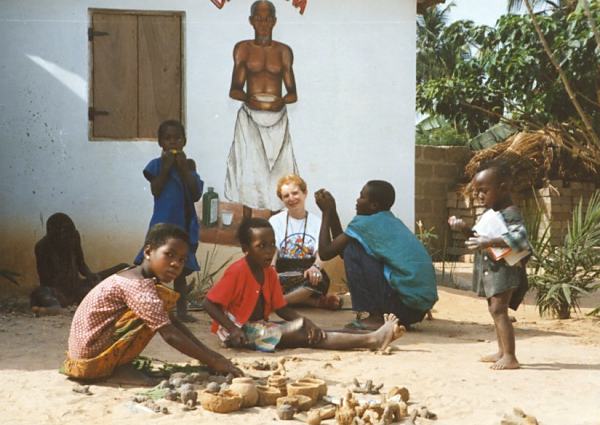

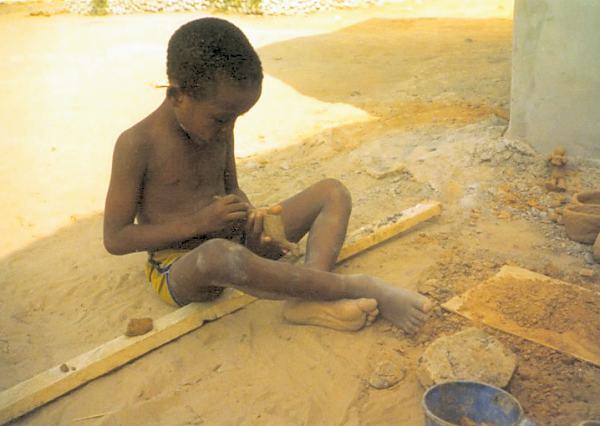

During workshops with the weavers of Kopeyia, Ellie teaches pottery to any village children who are interested.

During workshops with the weavers of Kopeyia, Ellie teaches pottery to any village children who are interested.The clay, brown, tan or black, is mixed with sand after being cleaned to add body. The Mpraeso potters use their clay very wet, much wetter than I'm accustomed to, perhaps to compensate for its rapid drying in the hot sun. Potters dig their clay from nearby deposits and carry it back to their yards, where they clean it of debris, wet it down and spread it out to dry. They sieve the dry, powdered clay before adding sand and rewetting back to a workable consistency. (A complete technical discussion on processing raw clay may be found in Michael Cardew's Pioneer Pottery.)

Once shaped, the bowl needs several hours drying time to the leather-hard stage before it can be burnished on the outside and the ridges scraped into the interior with the edge of a coin.

When I put down my bowl, Akua Manu was smiling. I thought it was because I'd made a good pot.

Felicia said, "She is very happy because you are serious about putting your hands in the clay. She says many white people come here and want to learn by watching, but don't want to touch the clay."

At that moment I wanted to spend the rest of my life in Akua Manu's yard making pots.

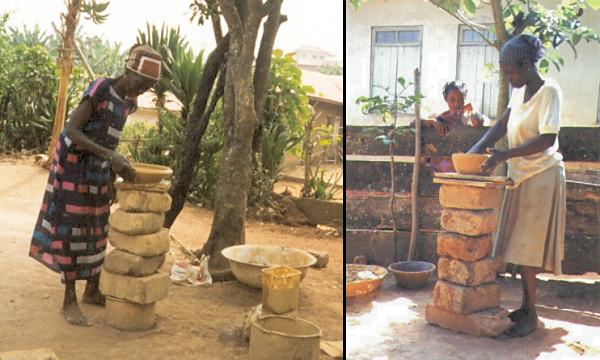

With African wheels, the pot stays still while the potter gets her exercise moving, often at a run, around it as she works. The pot rests on a board placed on top of a column of rocks built up to a comfortable height.

With African wheels, the pot stays still while the potter gets her exercise moving, often at a run, around it as she works. The pot rests on a board placed on top of a column of rocks built up to a comfortable height.Visiting in the potters' quarter

While waiting for our pots to dry, we visited some of the other potters in the neighborhood. The Mpraeso potters all live in one district, the older, more traditional-looking part of town. Houses there are mud brick or sometimes concrete, single-story, usually with two or three rooms and surrounded by some sort of fence marking the extent of their yards. The Yard is where most daily activities take place, cooking, socializing, child-care, and also pottery.

There were very few men around, since the women are the potters. Few men are interested, but when one (usually young) does attempt to learn pottery, the women laugh and make fun of him. They will say in confidence that they do this because they don't want competition from the men.

Almost every woman in this neighborhood is a potter. In the middle of each yard is a potter's wheel, or rather the local equivalent. This consists of rocks piled one on top of the other to a height comfortable for the potter while she is standing. At the very top is a piece of board that is the working surface.

Pit firing under the banana trees at Mpraeso. Pots are placed in a circle with fuel around them. For the typical black reduction effect, potters smother the flames with organic materials producing this cloud of smoke.

Pit firing under the banana trees at Mpraeso. Pots are placed in a circle with fuel around them. For the typical black reduction effect, potters smother the flames with organic materials producing this cloud of smoke.In America we handbuild using a banding wheel and stay in one spot, turning the wheel to reach different sections of our pot. In Mpraeso the pot stays in one place on the piece of board, while the potter walks, or more usually, trots around it.

I tried this technique in one yard we visited, attracting a large audience for my efforts. Trotting around in circles under the near-equatorial sun soon left me thoroughly dizzy and disoriented. Let me tell you, it's not only male potters the women laugh at.

Felicia and I wandered along the dirt paths leading from house to house, peeking over the fences to see what was going on in each yard. It was seldom dull. Children, goats, cats, dogs and assorted neighbors might be chatting and pursuing various activities, while the potter would be sitting under a tree making pots.

In one yard we saw several potters working, while some older women were cooking and watching the children. One particular woman, clearly the star, was circling her pot at a tremendous speed. She's known as Nzuma, after a famous boxer in Ghana, because she's so quick on her feet. She can make so many pots in so short a time that other potters will hire her to start the bases of their pots, which she then leaves to be finished by the residents. You could tell which yards she'd been to by the number of pots in them.

Houses in Mpraeso are more or less arranged in rows along a street, with the yards behind connected by a maze of dirt paths that people use going from house to house. In the more remote and traditional villages, such as the weaving village I bring artists to, houses are arranged in the old way in circular or semi-circular groupings around a common yard. Beautiful flowers grow wild in yards and along paths, but only the occasional vegetable garden is cultivated. Farms, at some distance from the village, are tended on weekends.

Pots for medical school

Mpraeso's pottery represents big business. The black, unadorned grinding bowls are sold in outdoor markets and along roadsides all over the country. People recognize which kinds of pots come from which place, and everyone has his favorites. No one gets upset if a pot breaks; the low-fired, fragile wares are expected to break, and a new pot is cheap enough. The pot market remains brisk.

Some potters simply pile their bowls on their heads and walk to market; others fill up a truck with pots; still others ship their work by bus. Sometimes the potters sell their own pots; sometimes they sell to a middleman (or woman) who then re-sells the pots at market. The outdoor markets are huge, and market women earn a lot of money.

A young Ghanaian sculptor concentrates on getting the details just right.

A young Ghanaian sculptor concentrates on getting the details just right.Several women told me they had put their children through school on their pottery earnings. One woman's son was in medical school in Boston. Bemused, I wondered if my income as a potter in Boston could ever put someone through medical school.

Pots are primarily functional items in Ghana, although in Accra you might see a few flowerpots. Because they are plainly utilitarian as well as fragile, not many pots are exported. Other Ghanaian crafts, of course, are exported all over the world.

At Akua Manu's I finished my pot from the morning and set it aside to dry. Pots are normally dried in a shed for several days before being fired.

Firing (pots) at dawn

There are no kilns as such. Pots are simply piled together on the ground, covered with dried dung, grass, sawdust, or whatever's available, and set ablaze with wood kindling.

Firings usually begin very early, often at dawn, to be well underway before the worst heat of the day. The smokey atmosphere produced by the dung et al. results in the rich, carbon-trap black of the finished ware.

My first visit to Mpraeso was over all too soon. On Sunday we had to return to Accra, leaving my still- damp pot behind. It would never survive the ride down the mountain.

I only hoped we would.

For further reading:

- Pioneer Pottery, Michael Cardew

- Coiled Pottery: Traditional and Contemporary Ways, Betty Blandino

- Smashing Pots: Works of Clay from Africa, Nigel Bailey

- The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah, Kwame Nkrumah